Matthew Vaughn’s 2010 film Kick-Ass is based on a 2008 comic book series of the same name, written by Mark Miller and illustrated by John Romita, Jr. While watching this film, I tried to keep our class discussion of Terry Zwigoff’s Ghost World in mind while watching this film. Both films are adapted from graphic novels; Kick-Ass, however, adds the superhero element in both its graphic novel and film. The main character, Dave Lizewski, wakes up one morning and decides to become a superhero, without any semblance of a real purpose or power behind his decision.

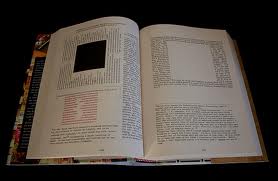

An example of a page from the original comic book series Kick-Ass.

Like Ghost World, Kick-Ass incorporates some of the drawings from the actual source text–or at least drawings that have the same style as the source text. Kick-Ass adds an additional element of an interactive comic, which serves the purpose of explaining the origin of the two “actual” superheroes of the movie, Hit Girl and Big Daddy. This sequence makes the viewer feel like they’re actually inside the comic book. It also breaks down the traditional montage sequence, giving it a substance most film montages cannot dredge up.

This clip shows Kick-Ass’ comic book montage within the otherwise live-action film.

The film also involves intertextuality, engaging with both itself and other texts. After Dave’s superhero persona gains notoriety, someone writes a best-selling comic book in his honor. The book on display in the shop some of the characters frequent is the actual book upon which the film was based.

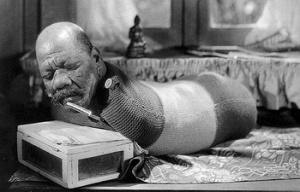

The film also incorporates considerable mention of and allusions to other superheroes. At one point, Kick-Ass’ voiceover indicates that “with no power comes no responsibility,” which is obviously a play on Spider-Man’s adage “With great power comes great responsibility.” Numerous other references include the 1978 Superman, the 1989 Batman, the 2000 X-Men, the 2005 Fantastic Four, and the 2010 Scott Pilgrim vs. the World. Furthermore, according to trivia on IMDb, Nicholas Cage purposefully talks like Adam West’s 1966 portrayal of Batman.

The film essentially subverts the expectations of modern superhero tales. Kick-Ass’ release coincided with the 2007 Spider-Man 3, and the 2008 film The Dark Knight, second in yet another Batman series. Kick-Ass provided a fresh look at the superhero genre, refusing to abide by the gore or language guidelines of a PG-13 movie like one of the other films of its genre. This film is not your child’s movie; its use of violence and offensive language likely shocked those entering the theater expecting another safe superhero film. By first engaging with the texts listed above, it then revolutionizes the genre by defying all expectations of a superhero flick.