Before watching Steven Spielberg’s A.I. Artificial Intelligence in class, I had seen the film numerous times (albeit not in the past three or four years). I had no idea that taking Film Adaptation would allow me to glean so much more from the film than I ever had before.

The biggest thing I hadn’t picked up on before was the religious undertone of the film. The source text, Brian Aldiss’ short story “Supertoys Last All Summer Long,” indicates that man created robots to cure man’s increasing loneliness in a nation with a strictly controlled birth rate. The film expands on that loneliness, equating man with a god who wants someone to serve him and love him unconditionally. A female colleague of Professor Hobby’s asks him, “If a robot could genuinely love a person what responsibility does that person hold toward that Mecha in return? It’s a moral question, isn’t it?” In response, Professor Hobby says, “The oldest one of all. But in the beginning, didn’t God create Adam to love him?” HIs colleague suggests that because this new robot can feel, man has an obligation to consider his feelings. But if the robots are being created solely to fulfill a void in a couple’s childless life, then unlike God’s selfless creation of man, it is a selfish creation. We see proof of this through David’s eternal, unanswered devotion to a mortal mother who cannot even fully love him back during her lifetime.

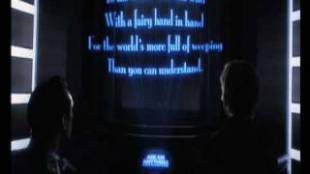

I was also able to discern intertextuality within the film that I previously hadn’t noticed. I had, of course, picked up on the Pinnochio element: Haley Joel Osment’s character longs to become a “real boy.” The less obvious references include those to the Wizard of Oz and William Butler Yeats’ poem “The Stolen Child.” David and Gigolo Joe journey to Rouge City, obviously a play on the Emerald City, in the hopes of Dr. Know answering all their questions. Furthermore, Yeats’ poem serves as a signpost along David’s way, beckoning him to follow the blue fairy to the ends of the earth.

Professor Hobby uses William Butler Yeats’ poem “The Stolen Child” to lure David back to the site of his creation.

Although many people take issue with the ending of the film, I had no problem with it either five years ago or just a few days ago. This most recent viewing, however, I realized that I didn’t quite understand the ending the first go-around. This time, I viewed the aliens/SuperRobots as suspicious characters; they had the ability to “recreate” almost anything from David’s memory, but these ultimately proved to be just extremely believable manipulations of the mind. Thus, I viewed Monica’s recreation with skepticism: true, she could love David in a timeless world free of the complications of Martin, Henry, and the inevitability of time, but is that a real love? And if the other depictions of David’s memory are ultimately false, might not Monica and her love be just another slight of hand?

David is given one more day with Monica, only to lose her once again.

I also picked up on the film’s implication that David dies at the end of the film. At the end of her one-day lease on life, Monica falls to her final sleep, and the narrator tells the audience that “David went to sleep too. And for the first time in his life, he went to that place where dreams are born.” After reading the trivia on IMDb, I learned that Haley Joel Osment suggested his character not blink to prove his mechanic nature. Spielberg loved the suggestion, and instructed all of the robot characters to do the same. This sheds new light on the fact that David closes his eyes and goes to sleep with Monica; perhaps he too will never open his eyes again. Before rewatching the film and learning this piece of trivia, I assumed that David would go on living his life in devotion to a mother whom he was now certain he would never again. In this way, the film gives David peace and releases him from the emotions which man selfishly made him feel. In a roundabout way, the film answers the question posed at its beginning, suggesting the implications of shirking the responsibility for its own creation. Like Frankenstein and his monster, man had no place trying to play God for his own scientific gains.